This mostly non-technical post is the first of a series on how AI could go badly for the world and why we should consider slowing down. The post is going to focus on what kinds of systems we’re going to be discussing, how progress in AI has come along, and how things have already gone somewhat wrong.

The series is going to concentrate on the risks from human-level (or above) AIs (i.e., AGIs). This focus isn't because I think the risks from current AIs are unimportant. Actually, I think they are extremely important because we don't want to exacerbate existing injustices or create new ones.

At the same time, I think some of the issues we're facing with current AIs are symptomatic of fundamental problems in AI development. With the more advanced AI systems that are coming fast, these fundamental problems will likely soon rear their ugly heads in ways that we are less used to dealing with. We should get the ball rolling on preventing them.

Here’s the roadmap for this post.

I’ll introduce some new terminology to sidestep some thorny debates about the term AGI.

I’ll give a qualitative description of the progress we have seen in AI in the past several years.

I’ll talk about how things have already gone somewhat wrong, and hint at how things could get worse.

What is a WIDGET?

By a human-level AI, I mean an AI that could accomplish most or all economically valuable tasks as well as human could. This definition includes tasks like coding, convincing/deceiving people to get them to do what you want, delegating tasks effectively, etc. I could also use the term AGI and it'd fit just as well. By agent, I mean something that can act autonomously over a long time horizon to achieve some goal.

There are some reasonable objections to the notion of AGI that one could raise.

Human intelligence is about more than just solving problems.

There's no such thing as general intelligence because intelligence is specialized.

Agency involves sentience/intent/desire/etc.

Some of the objections seem correct to me. But none of the objections is relevant to risks from AI. The precise definitions of intelligence, generality, or agency don’t matter because the focus of this discussion is on the risks posed by systems we are actually building, and systems we will likely build in the next decade or so. We can have productive discussions without precisely defining every term because context will make things clear, and if it does not then I will disambiguate.

To sidestep these debates about intelligence, generality, and agency, I'm going to use a different term.

WIDGET stands for Wildly Intelligent Device for Generalized Expertise and Technical Skills.

I'm going to use WIDGET (widget hereafter) to refer to a system with the following properties.

The ability to plan over long time horizons, on the order of months to years.

Human-level or above fluency with language and language-based tasks, including coding.

Competence in interacting directly with the world digitally, rather than having interactions mediated through humans. This competence includes a general understanding of how the world works, but may not include skills like physical manipulation of objects.

As an example of a widget, consider a system that could code up a web app, interact with people over the web to facilitate a business transaction, review a legal document, and run the operations of a company.

A widget is not necessarily an AGI since an AGI could do some things more capably. For example, a widget might not be capable of performing tasks that require physical coordination, or of coming up with new, correct theories of physics on the spot. However, an AGI seems likely to be able to do all that a widget could. To accomplish all economically valuable tasks as well as a human could, it seems that an AGI would have to have all three properties listed, since they are properties that humans have. The rest of this piece is going to be about why widgets pose significant dangers and why we should pause building them. If we believe this claim, then we should also believe that we should pause building AGI since all AGIs are widgets, even though not all widgets are AGIs. I'm also going to use the word system to describe systems (i.e., AI systems) that have some of the aspects of widgets, but are not quite there yet.

Progress is wild and will probably continue to get wilder

Many people have written extensively about the rate of progress in building widgets. We can look at the amount of computation by year, for example.

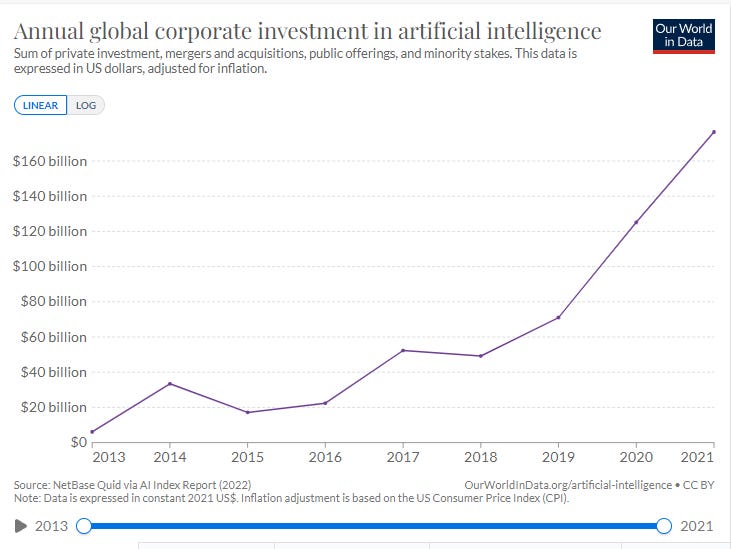

Or at private investment.

But throwing money and computation at a problem doesn't necessarily translate into progress. Another way to look at things is to look at what our current systems can do.

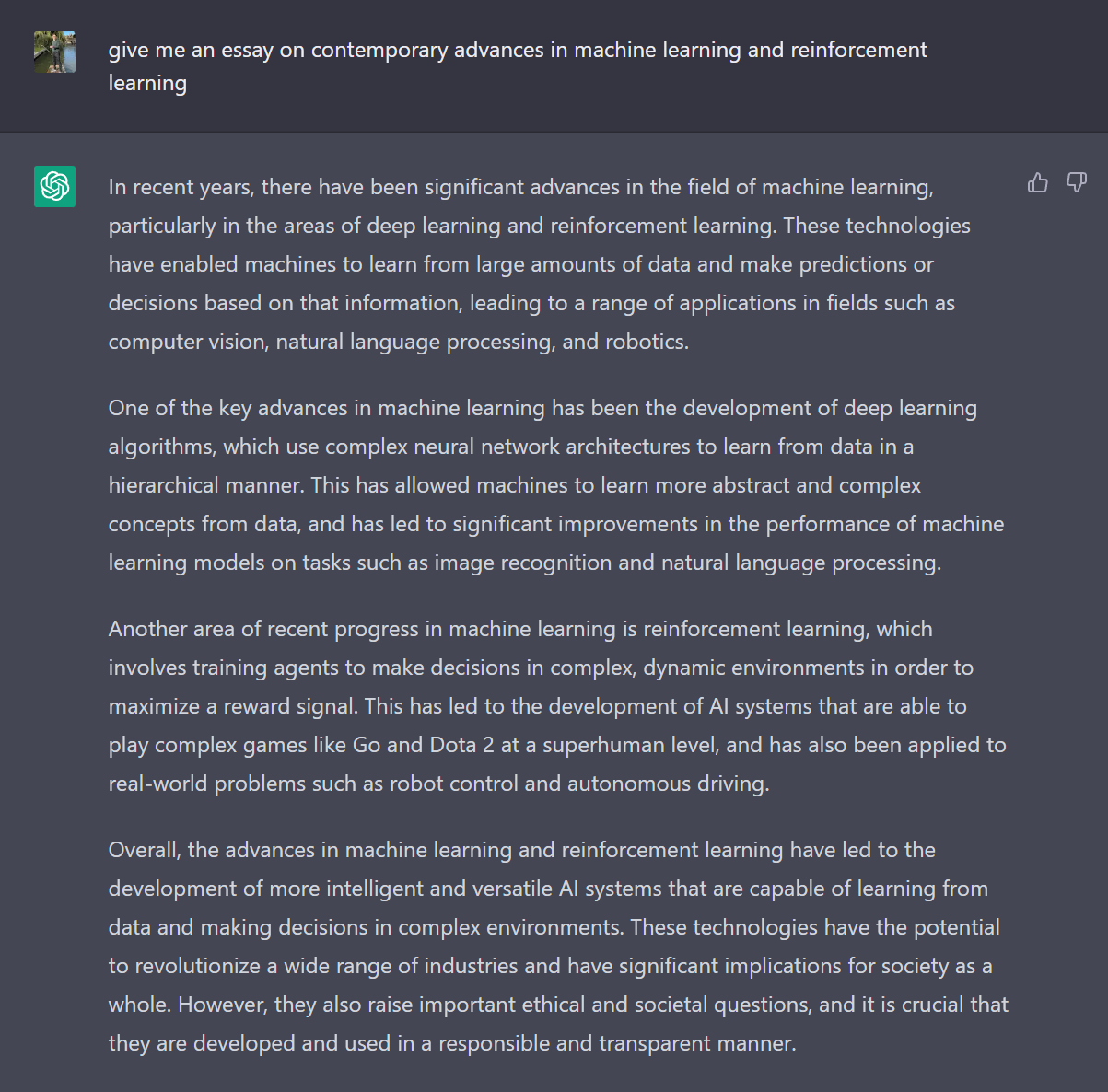

The essay above was generated by a system, ChatGPT, that was trained to predict the next token (read: word) on a bunch of internet and other documents. That's it. A simple objective (and a relatively simple training procedure) suffices to produce a conversationally capable system. At no point did we tell the system how exactly to write an essay, but there it is. Writing an essay for humans usually requires a bit of planning and forethought, but it seems like ChatGPT can do so fairly easily. There are lots of other things you can do. I encourage you to try the system out for yourself.

People have recently also made systems that can play diplomacy with press. Diplomacy is a multiplayer strategic board game that involves negotiating with other players and taking over territories. With press means that the game allows text or verbal communication between the players, for example for making deals. The recent diplomacy progress means that the system can communicate with humans to convince (or deceive) them into taking particular courses of action, and actually succeeds in doing so a good proportion of the time.

AlphaFold has upended protein structure prediction, which is essential for things like developing novel drugs. AlphaZero taught itself Chess, Shogi, and Go, and plays them at superhuman levels. Its (inferior but still superhuman) predecessor, AlphaGo (which only works on Go), came up with the totally unexpected move 37 to beat Go master Lee Sedol.

All of this is absolutely nuts.

We have systems with some of the properties that widgets are supposed to have, to some extent.

We have systems that can plan. Some systems can plan over long time horizons, but are so far limited to games that are much simpler than the real world. Other systems seem to be able to plan in more complicated environments, but cannot yet plan very far ahead.

We have systems that are fluent with language and some language tasks.

We have systems that interact directly with portions of the world, rather than have their interactions mediated through humans.

It's fairly easy to find thing that our systems cannot do, but the point is that barrier after barrier keeps falling year after year. GPT-2, a predecessor of ChatGPT, was released in only 2019 and is far less capable. Play around with it and see. Our systems certainly have limitations, but billions a year are being spent to overcome these limitations. Mind-numbing amounts of computation and data are used. It seems like a fairly safe bet that our systems will continue to get better at a rapid pace.

The next point is key to how we are designing our systems.

4. We don't tell a system how to accomplish a goal. We simply give it data, computation, a general architecture, and general training algorithm. At no point do humans give a low-level specification of how we want a specific task accomplished.

It’s extremely hard to provide low-level specifications of tasks. Just think of how you could build, in code, something that could hold a conversation with you. How would you even begin to build something as capable as ChatGPT? Even if we could provide low-level specifications for every system we built, it would probably be prohibitively labour-intensive than how we’re building systems now.

So what could go wrong?

Things have already gone wrong

Recommender systems, like those that power Twitter and Facebook feeds have been blamed for increased radicalization, user manipulation, and a decrease in our collective well-being.

It's difficult to know the precise degree to which the recommender system itself, as opposed to the economics of YouTube for example, is responsible for adverse societal outcomes. Since recommender systems are proprietary, it's also difficult to know how exactly they work.

At the same time, we can tell what seems to be a plausible story with some support. A system that optimizes for user engagement, because we don't tell a system how to accomplish a goal, does whatever it can to make users engaged, whether it be through making them doomscroll, be angry, or spread misinformation. Moreover, a recommender system that surfaces and encourages infectious, unproductive disagreements plausibly gets more engagement than one which emphasizes consensus.

Not telling a system how we want to accomplish a goal seems bad, so why don’t we just tell it what to do? The answer is that we often have no idea how. What does it mean to make users well off? How would we even measure it? People are working on this difficult problem, but it’s much easier to measure a proxy like the number of clicks. It’s plausible that the number of clicks is correlated with user well-being since users would probably click on things that they genuinely enjoy. At the same time, a proxy remains a proxy. Optimizing for something that isn’t what we fundamentally care about could lead to harmful side effects. For example, the number of clicks could correlate with material that is sensational but potentially damaging to user and societal well-being, such as misinformation about COVID-19.

Goodhart’s law is the empirical tendency for proxies to become worse at tracking the underlying metric we care about once we start optimizing. In addition to user engagement with social media, another example is the Volkswagen emissions scandal, where Volkswagen programmed its engines to turn on emissions controls only during lab tests, and otherwise turned them off to allow better fuel economy. The proxy was the verified measurement of emissions at a specific moment in time, rather than all the time.

As a proxy becomes worse at tracking the underlying metric, the possibility of negative side effects could increase. If we optimize really hard for this worse proxy, we could be driving society very hard down an unknown direction. This possibility sounds a little scary.

Despite the fact that we only have proxies for user (and societal) well-being, the profit incentive still exists! If optimizing for user engagement is what encourages users to use your product and no regulator is going to tell you off, well so be it. Optimizing more for the proxy increases profit even more, even though it probably increases negative side effects too by Goodhart’s law. It’d be harder to pull this trick in our current environment, but Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram already pulled the trigger more than a decade ago. We’re left cleaning up the mess.

Let's go back to the four things that I mentioned above.

Long-horizon planning.

Fluency with language and language tasks.

Direct interaction with the world.

We don't tell a system how to accomplish a goal.

Recommender systems satisfy 3 and 4. A recommendation directly affects the person to whom the recommendation is given. At the moment, recommender systems do not satisfy 2, since we don't yet have personalized chatbots recommending things to us. We don't have solid evidence on 1 since we don't have public access to most of the big recommender systems. But my experience with 1 in my past research is that it has been quite hard to implement, so it seems unlikely to me that systems up until very recently have had 1. So systems with likely just 3 and 4 have possibly contributed to the rise of right-wing extremism, political violence, and social malaise.

Now imagine a recommender system that was also a widget. With long-horizon planning, it would be that much more capable at manipulating you to maximize the company's score of user engagement. It might study your profile in detail, using its fluency in language to strike just the right tone when recommending you a post to read. It would be your friend in all appearances, yet it would be built for the sole purpose of treating you as a means to the profit-driven ends of a democratically unaccountable corporation.

Next up

Next time, we’ll talk more about how else widgets could cause damage.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Anson Ho, Josh Blake, Hal Ashton, and Kirby Banman for constructive comments that substantially improved the structure, clarity, and content of the piece.